One of the difficulties of writing science fiction for the modern age is the expectation of a certain level of scientific realism. If you look at older science fiction from before the space age, there wasn’t a huge concern about if it was scientifically accurate or not. Take Edgar Rice Burroughs’ celebrated Barsoom series; while incredibly fun and wonderfully written, the science in the books hardly holds up to modern scrutiny. That being said, if your only experience with Barsoom is the film John Carter, I highly recomend picking up the novel series and having a read.

As our knowledge of science has improved, the expectation that science fiction be more scientifically accurate has also increased. There is the expecatation by audiences, whom are more educated than ever before, that the author has done a level of research on their topic. Andy Weir’s The Martian was applauded because the majority of the science in the film holds up really well. James S.A. Corey’s Expanse series, both the television and the novels, feels so intense because it is so increidbly believable in regards to the technology and the where humans could be in the very near future. This scientific realism and accuracy allows for the suspension of disbelief to not be on the mechanics of the film/show/book but rather in the plot, allowing the viewer/reader to be more absorbed in the story and less in the way the world that the story takes place in works.

When I first started writing Haven Lost, I didn’t really have too much of the science in mind. I had the plot and I knew the setting would require a few different worlds but I had spent little time thinking about the actual science behind the Haven star system. As I continued working on the manuscript I began to acknowledge how vital it is for certain information to work.

The largest example of this was making the Haven start system work in a universe that is defined by our understanding of modern physics. I started with the three planetary bodies that were the most important: The star Haven which is a white-ish blue start and larger than our own Sol; the planet Dawn which is roughly Earth sized but that the majority of it is covered in snow and ice; the planet Dusk which is a little smaller than Earth but covered in a massive jungle with a single large tide-locked moon called The Watcher. I would eventually go on to add a few more planets, such as a Mercury-esque planet that is close to Haven, a large gas giant in the outer parts of the system, and a white dwarf binary star at the outer edges of the Haven system. There is one more location in the system but it is a bit of a spoiler for part of the story so you’ll just have to read about it once I finish Haven Lost.

I will be the first to say that I am not a physicist and not an astronomer. I have a basic grasp of both concepts but my understanding of most of it is pedestrian at best. The first thing I needed to do was make sure tha the two major planets, Dawn and Dusk, were both in the “Goldilocks” zone of Haven. Named after the fairy tale of the same name, The Goldilocks zone is the area of space around a star where life could potentially survive. Too close to the star and the planet is cooked. Too far away and it is frozen. Dawn, being an icy planet, needed to be right on the outside edge of the Goldilocks zone an Dusk, being a humid jungle world, needed to be in the inner half of the Goldilocks zone. I also knew that Haven was not only a larger star, but also a hotter star than our sun so it would obviously have a different Goldilocks zone than our own. For reference, the most recent estimate of the habitable zone for Sol is from roughly .95AU (an AU is an Astronomical Unit or the distance from Earth to the Sun) to 2.4AU.

Haven A is 1.6 times as massive as the sun, 1.64 times the radius of the sun, has a temperature of 7200 K, and is 6.485 times as luminous. I used a combination of tools to find this data. First was a star table, which tells you what type of stars could potentially support life. Haven A is an F0 Class star; essentially the biggest and hottest that is capable of supporting life. I also used a luminosity calculator to determine how bright Haven A is. With that information I was able to plug data into a Habitable Zone calculator to find out exactly where Dawn and Dusk could lie in the system to be able to support life. Haven A’s habitable zone ranges from 1.89 AU to 4.413 Au, with an ideal range of 2.39 AU to 4.192 AU.

What did this mean for my planets? The first and most noticeable difference was that these were significantly further away from Haven A than Earth was from Sol. This meant that the years would be much longer. Based on the climates of the two planets I placed them at opposite ends of the Habitable zone. Dawn, being an icy planet, has an orbital distance of 3.5 AU. Dusk, a jungle planet, was much closer at 2.4 AU. Using an orbital period calculator I was able to determine that Dawn, which is slightly smaller than Earth, takes 1,890 Earth Days to complete a revolution around Haven A. Dusk, slightly larger than Earth, takes 798 Earth Days to complete its revoution.

My first thought when I had this information was that I had everything that I needed. However, there was something that was bugging me that I couldn’t put a finger on. I stepped away and focused on my characters and writing character sketches when I realized the major problem: A day on Earth is not the same length as a day on Dawn, just as a day on Dawn is not the same length as a day on Earth. This was without a doubt the hardest part of world-building I have done so far trying to nail down these calenders.

The first step was to figure out how many Earth hours it would take for each planet to complete a singlular rotation. I had to use what information we knew to then determine what information we didn’t know. What did I know? I knew that Dawn had 1,890 Earth Days in a Dawn Year. I also decided that there were 18.75 Earth Hours in a Dawn day. what I didn’t know was how many Dawn Days were in a Dawn Year. I also couldn’t find a calculator that really helped on this so it was down to me to make my best shot at it. First, I looked at the terms we had: Dawn Days(Dd), Dawn Years(Dy), Earth Hours(Eh), Earth Days(Ed). 1 Dy=1890 Ed. 1 Ed = 24 Eh. 1 Dd = 18.75 Eh. Time for some Algebra!

1 Dy = 1890(24)

1 Dy = 45,390 Eh

1 Dy = 18.75Eh * x Dd

18.75x=45390

x=45390/18.75

x=2419.2

There are 2419 Dawn Days in a Dawn Year.

This was a huge breakthrough for me. This was a planet with a people with their own culture; they wouldn’t be measuring their days based on Earth time so it was important that I was able to figure out their own system of time. Now that I had how many times Dawn rotates over the course of a single Dawn year I could play with the other numbers. On Dawn they use a decimal based time system: 10 hours in a day, 100 minutes in an hour., 100 seconds in a minute, keeping in mind that a Dawn second does not equal an Earth second. There are 24 months in a year, each with 100 days in it. The final 19 days of the year are what is known as Holiday.

I repeated the Process for Dusk. Dusk ended up with 798 Dusk Days in a Dusk year. Instead of months, they used a quarterly system, each quarter with 200 days except for the final quarter, which has 198. Their day is also 10 hours in length, but their 10 hours is significantly longer than Dawn’s 10 hours since a Dusk day is roughly 32.25 Earth hours in length.

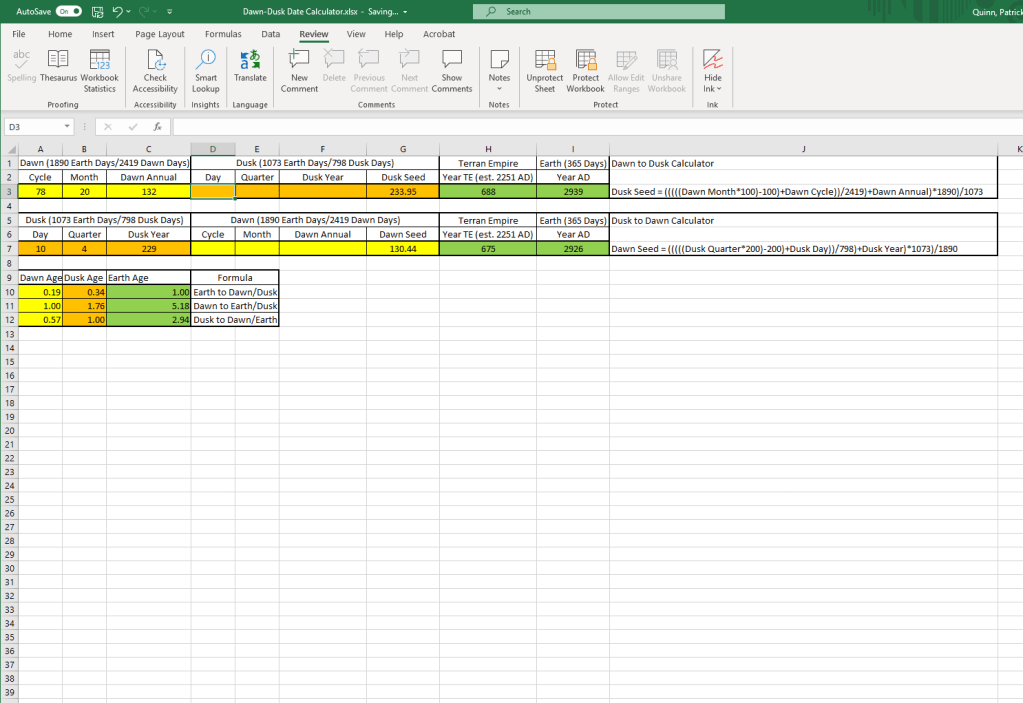

On top of this, I needed to make sure there were calenders for both planets as well. Considering they have two different length years, it made sense for them to have to different length calenders. This would once again require a whole bunch of math to figure out. For my sanity, I made the determination that both planets were colonized on the same day in the ancient past. Figuring out the calendar for Dawn was easy; pick a date and start there. Let’s assume that the date that Haven Lost begins is on the 42nd day of the 13th month of Dawn year 134. I had to use that information to figure out the date and time on Dusk. Once again, it came down to combining like information. The chart below has the data that I knew:

| Dawn Day | Dawn Month | Dawn Year | Dusk Day | Dusk Quarter | Dusk Year |

| 42 | 13 | 134 | x | y | z |

Since I made the determination that both planets were founded on the same day, it meant that the Day 1 of Year 1 on both planets was the same. I then looked for information that I knew on both. Based on the orbital period calculator I used before, I knew how many Earth Days were in every year for both planets. Dawn had 1890 Earth Days/year and Dusk had 1073 Earth Days/year. Math time again!

1890(134)=1073x

253260=1073x

x=253260/1073

x=236.03

This allowed me to fill in some blanks in the table. It was Dusk Year 236 and we were .03 of the way into the new year. .03/1073=32 Earth Days. We could use our previous formula to determine how many Earth Days are equivalent to How many dusk days.

32 Earth Days * 24 Earth hours = x Dawn Days * 32.15 Earth Hours

768 = x * 32.15

768/32.15 = x

x=23.88 Dawn Days

This would mean that it was in the 80th minute of the 8th hour on the 23rd day of the 1st Quarter on Dusk. Now we could complete the table from before.

| Dawn Day | Dawn Month | Dawn Year | Dusk Day | Dusk Quarter | Dusk Year |

| 42 | 13 | 134 | 23 | 1 | 236 |

My goal with Haven Lost was to have these planets feel like real places with real cultures. As we know from our own history, knowing dates and times and places is paramount to understanding our own cultures. Having independent calenders may seem like an enormouse waste of time but to me and the characters I am creating, it is their history and all they know. It was important to understand that these planets weren’t just offshoots of Earth but were their own living and breathing planets.

If anything, I hope this gives you an idea into the level of work that goes into writing quality science fiction. For sci-fi authors, especially now, the science is every bit as important as the fiction and it is important that we get it right.

Thanks for reading and please leave a comment below with your thoughts!

Leave a comment